Raging Bull (1980) Review

Raging Bull (1980)

Director: Martin Scorsese

Screenwriter: Paul Schrader, Mardik Martin

Starring: Robert De Niro, Joe Pesci, Cathy Moriarty, Frank Vincent

Dark ropes foreground a misty arena where a lone fighter shadowboxes. Camera bulbs flash in the back, capturing what has become nostalgia for the fighter. He stands alone in a backroom of a club, rehearsing a poem, a far cry from the young, energetic boxer. Jake LaMotta was a real and terrifying individual whose story is antithetical to American sports mythos. His bouts in the ring were bookends to unceasing fights with his family. He had no respect or trust for anyone in his community. So even in his hazy dreams and memories, Jake LaMotta is alone, fighting an endless battle against everything and nothing.

Raging Bull is not just considered among Martin Scorsese’s best films, but among the best American films ever made. Contemporaneously, it represented a maturation for the young director, who, when faced with his own mortality, put together an antihero sports picture that defied the genre’s conventions. Robert De Niro’s intense application of the Method was a popular point of discussion in press and critical writing around the film. And Thelma Schoonmaker burst onto the scene as the film’s editor, winning a Best Film Editing Oscar on her first major feature film as the editor. Every aspect of the film works towards creating a Modern Impressionist masterwork.

Robert De Niro was actually the driving force behind Raging Bull’s creation. He brought LaMotta’s autobiography to Scorsese, convinced the book would make a great film, and hounded the director about it for years. Scorsese finally relented after finding himself relating to LaMotta’s self-destructive tendencies. After several screenplay rewrites, filming and post-production lasted over a year due to Scorsese’s perfectionist approach to editing (though Schoonmaker argues film editing was eased due to Scorsese’s thorough planning and execution of scenes). Scorsese was inspired by the boxing newsreels of his childhood, and aimed to update the boxing movies from 1940s Hollywood to the gritty standards of the American New Wave.

It’s difficult to describe the plot beyond “it’s about the life of boxer Jake LaMotta.” While the events are mostly told chronologically, there’s no specific goal or endpoint the story strives towards. Instead, the film is driven by LaMotta’s rage, each scene giving us a deeper look into his internal reality. It’s a portrait of the patriarchy’s violent affects on men and women, how the drive to win poisons American society, how achieving doesn’t solve anything.

De Niro exquisitely expresses this existential conflict through his Method approach. De Niro lived with LaMotta, incorporating his everyday reactions and mannerisms into the performance. He learned to box and won two of the three matches he participated in. He wore prosthetics that helped remove Robert De Niro from the picture, and famously gained 60 pounds to better resemble the older LaMotta. This was the kind of performance where De Niro stayed in character on set, only responding to being called “Jake” or “Champ”.

His Method technique helped to make the performance engrossing, visceral, and memorable. De Niro’s transitions from calm to angry feel natural, like in the scene where Jake accuses his brother Joey of sleeping with his wife. The two are making small talk when Jake begins to question Joey about an incident at a club, followed up by insinuations and accusations that lead to a physical confrontation. Consciousness of the reality that Jake LaMotta was actually a cruel brother and husband overcomes De Niro’s because of his raw portrayal that were a product of his study and practice.

That rawness is one place where Raging Bull stands out from Hollywood classics like Body and Soul (1947) and The Set-Up (1949). The performances in 1940s Hollywood were externally motivated and rather composed and rehearsed. Production Code standards affected how characters could act and how their stories unfolded due to their actions. Violence was limited. While Scorsese is often cited for his exceptional violence, seemingly for the sake of it, it brings a level of grounding realism to Raging Bull that couldn’t have existed in the 1940s. LaMotta as a despicable protagonist is a better representation of the attitudes and culture of the era rather than more sanitized and sentimental Hollywood portrayals. The attempt to be honest about the darkness of the human experience from someone who was a “champion” is part of the film’s elevation of the art of the sports drama (though it wasn’t the first to do so).

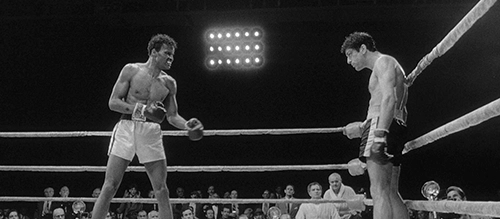

The cinematography and editing are the other major part of Raging Bull’s innovation in the genre. Dr. Todd Berliner wrote of what he termed the visual absurdity of Raging Bull. The film is filled with nonsensical sequences – an example is during a fight where an opponent throws a right hook, LaMotta is hit with a left hook, and the proceeding cut to the opponent follows through on the right hook. It doesn’t make sense and is disorienting to any viewer. Another fight creates the feeling of being in heat through changing focus and slow-motion shots to create visual mirage effects. The dolly zoom on Sugar Ray Robinson, taking him from light into the shadow cast by the harsh arena backlighting, is the most aesthetically pleasing shot in the film. These techniques intimately display LaMotta’s inner reality in ways that pushed the boundaries of Hollywood style. These more extreme methods are contrasted with the black-and-white photography – which resembled the classics and distinguished it from Rocky – and documentary-style sequences that give the film some simplicity and logic. It’s an excellent balancing act that Scorsese, Schoonmaker, and cinematographer Michael Chapman pulled off.

Another good choice for the film was the casting of lesser-known performers in the film’s main roles, which also plays a role in grounding De Niro’s presence. Cathy Moriarty as Vickie LaMotta is such a standout for an eighteen-year-old in her first film. The young actress has the poise and image of a classic Hollywood actress, and is very capable of playing both the younger and older versions of her character. Two other unknowns were Joe Pesci and Frank Vincent, who became staples in Scorsese’s filmography. The pair had worked together on stage as comedians and musicians and had roles in a TV mob movie that De Niro saw. Pesci and Vincent were cast as Joey LaMotta and the local gangster Salvy, beginning their own legacy as mafia movie icons.

When looking at a filmmaker like Martin Scorsese, it’s tough to parse out which of their films is the “best”. He has worked in so many genres and styles over such a long period, and he has had a massive impact on American and global cinema because of his love of the art form. Raging Bull is assuredly among his best, though. It is a peak in the crescendo of auteur-driven cinema of 1970s Hollywood (a binary opposition to Heaven’s Gate). The film’s imagery, style, and performances work in concert to great effect, and help to create a timeless classic that has love and respect for the movies that came before. Anyone who loves cinema should watch Raging Bull.

Score: 24/24

Recommended for you: The Importance of Expressionism in ‘Raging Bull’